Motivational Inversion

This correspondence from the early Reciprocality discussion group examines how the “Ghost Not” may distort the way culture understands selfishness and altruism, and likewise rationalism and spirituality. The material is preserved here as a historical discussion, lightly edited for clarity while retaining the original argument.

Motivational Inversion

Alan Carter

A familiar science-fiction trope shows a crew struggling with a complex technical failure, trying many different adjustments before finally “realigning the detector array,” which instantly solves the problem. The natural question is: why not do that first?

The idea explored here is similar. If the Ghost Not exists as a pervasive cognitive inversion, then much of the confusion surrounding moral language may result from beginning with an inverted picture of reality.

The universe contains many non-zero-sum situations. Two people exchanging complementary resources both benefit. Biological ecosystems expand complexity through cooperation, and over cosmic time simple structures give way to richer ones. These are not special cases but characteristic features of reality.

The Ghost Not changes how such situations are perceived. When opportunities cannot be seen, scarcity becomes the assumed condition. A world of cooperation is interpreted as a world of competition. In that mistaken model, one person’s gain must be another’s loss.

Children raised within this view cannot easily be taught positive reasons for social behaviour. Instead they learn avoidance: punishment discourages harmful actions, but no clear account explains beneficial ones. “Not anti-social” is treated as equivalent to “social,” even though it produces none of the cooperative benefits that real social interaction provides.

Within that framework two ideas emerge. “Selfishness” becomes defined as benefiting oneself at the expense of others, while “altruism” is defined as benefiting others at the expense of oneself. No third possibility is recognised.

In practice people do not wish to harm others, but neither do they wish to destroy their own well-being. Trapped between the two false options, behaviour becomes indirect and defensive. The result is what the discussion calls anti-altruism: rigid withholding of benefit, justified by the assumption that any advantage given away must be a loss.

The alternative error is anti-selfishness: the belief that harming oneself must automatically help others. Neither approach works well because both depend on the same mistaken assumption that reality is fundamentally a zero-sum competition.

The proposed inversion is simple. If the universe is primarily non-zero-sum, then improving one’s own environment usually improves the shared environment as well. Individuals exist within overlapping systems. Enhancing one part tends to enhance others.

In that case, authentic self-interest and authentic benefit to others converge. Actions that genuinely improve one’s situation typically produce measurable improvements for others too, because both occur within the same network of consequences.

This does not mean that every action benefits everyone, nor that harmful behaviour disappears. Rather, it suggests that sustainable benefit tends to be mutual. One can often evaluate whether a plan serves oneself by examining whether it plausibly benefits others within the same environment.

The discussion gives a practical example. Excessive administrative safeguards designed to prevent minor abuse can cost more than the abuse itself and reduce the effectiveness of assistance programs. Removing counterproductive barriers may serve both taxpayers and recipients simultaneously. The interests are not opposed but aligned once the system is understood correctly.

The Epilogue

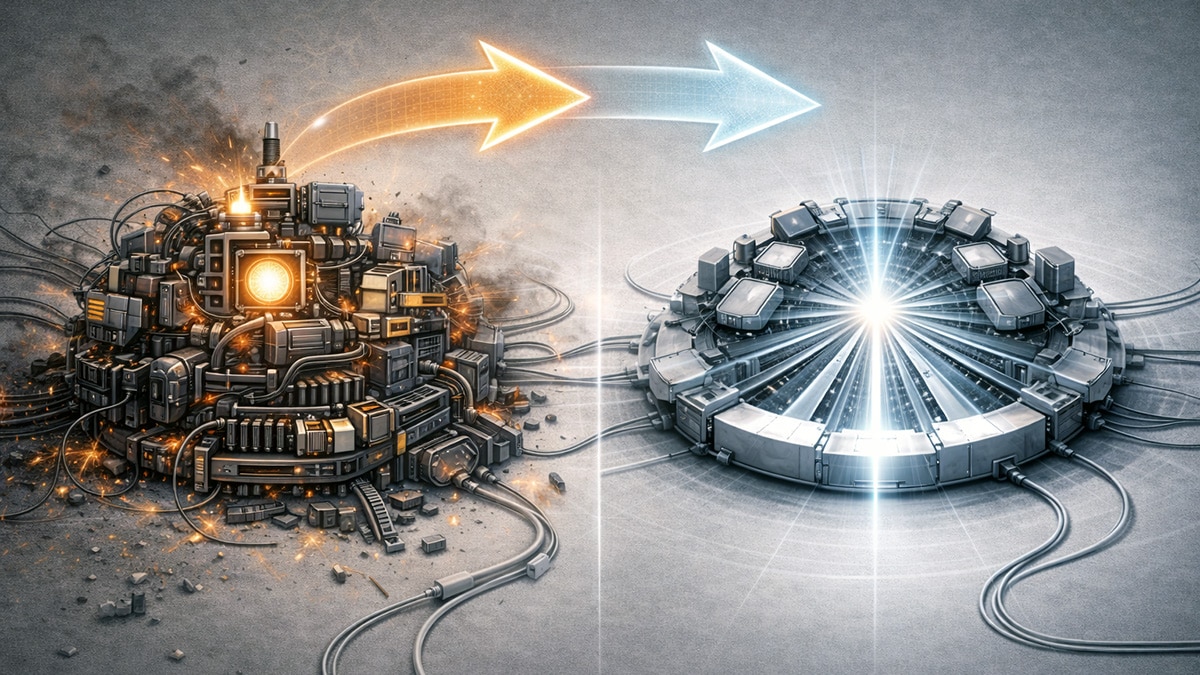

The central claim can be expressed symbolically. If the conceptual model is inverted, conclusions derived from it are also inverted. The error resembles a figure-and-ground illusion: the same elements appear different when interpreted in reverse.

A well-known physics anecdote illustrates the idea. A rotating sprinkler spins when water is expelled. When suction is applied instead, intuition suggests it should spin in the opposite direction, yet it largely does not. Reversing the apparent direction does not simply produce the opposite behaviour because the underlying conditions differ.

The analogy suggests that ethical confusions may arise from treating conceptual opposites as symmetrical when they are not. Turning the conceptual system inside out alters the answers.

The discussion concludes that pursuing one’s own effective well-being need not harm others. In a connected world, improving the conditions under which one operates can simultaneously improve the conditions experienced by others. If this occurs, mutual benefit is not accidental but expected.