The Third Age of the World: Form

You pick up a paper. You read a name. You go out and encounter it again. You meet a friend you had only just been thinking about.

Part of The Third Age of the World — return to the main guide for the full series and chapter index.

Galaxies, Trees and Heartbeats

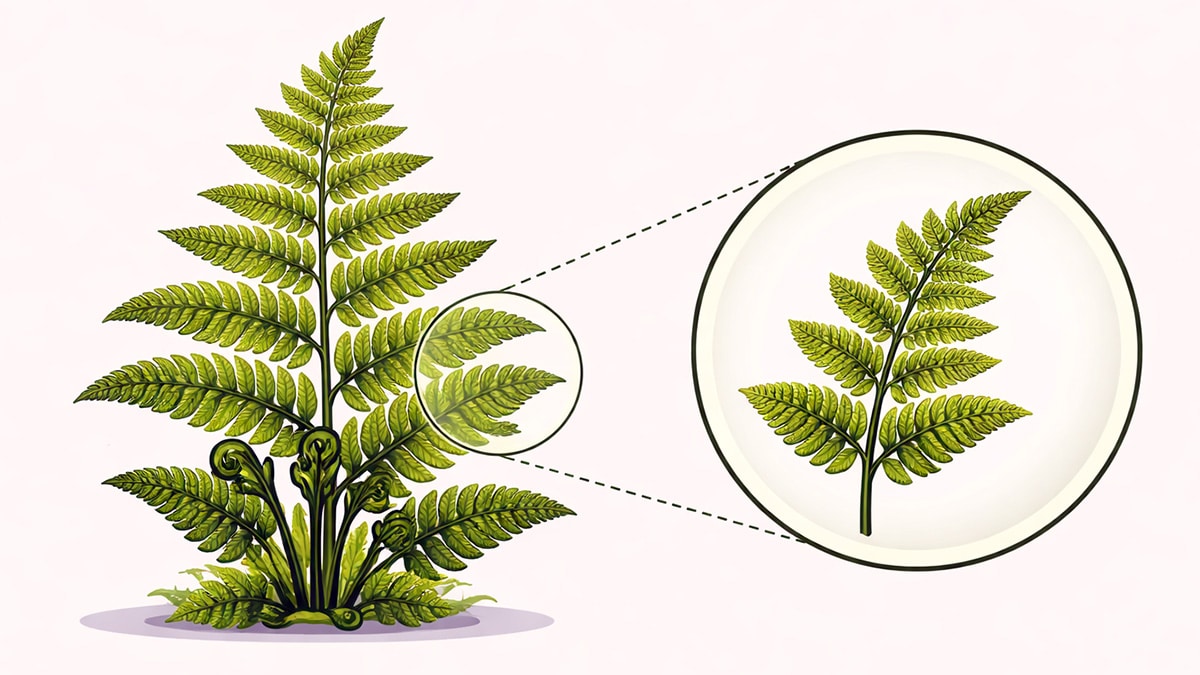

Across nature we repeatedly encounter structures that resemble themselves at different scales. A fern branch resembles the whole plant. River systems resemble the branching of trees. Coastlines look similar from an airplane or from a hilltop. These are examples of fractals: patterns generated by simple rules repeated many times.

Sometimes repetition produces something visually simple. Other times it produces astonishing complexity. The Mandelbrot set, created by repeatedly applying a simple mathematical operation, shows a boundary region where order and unpredictability meet. Nearby starting points produce dramatically different outcomes, yet coherent shapes still emerge. When we zoom deeper, miniature versions of the larger pattern reappear.

This teaches three important lessons. First, local behaviour can be unpredictable even when governed by strict rules. Second, structure can emerge out of apparent chaos. Third, large-scale organisation can be encoded within a very simple process.

Natural landscapes behave similarly. Smooth mountain ranges contain smaller smooth hills and valleys. Jagged ranges contain jagged formations at every scale. Different geological processes create rocks and cliffs, yet their overall roughness is consistent across size. For this reason computer graphics can simulate terrain using fractal mathematics and still look realistic.

Fractal structure appears everywhere. The spacing of heartbeats varies in patterned ways. Dripping taps form repeating timing structures. Stock-market charts show similar jaggedness whether plotted over days or decades. Even the large-scale distribution of galaxies follows clustered patterns rather than uniform spread.

When a simple rule repeated across scales can produce enormous complexity, it becomes difficult to identify a single cause behind each example. Rather than forcing fractals to fit earlier theories, we may need to treat patterned self-similarity as a basic feature of reality. Classical mechanics still predicts a thrown ball accurately, yet deeper descriptions reveal more general principles operating beneath the smooth motion.

Modern physics already hints at this. Richard Feynman’s path-integral formulation of quantum mechanics considers every possible path a particle could take. Those paths are irregular rather than smooth. Yet when averaged appropriately they produce the familiar behaviour described by Newton’s laws. A deeper description contains the simpler one within it.

The world may therefore be layered. Smooth behaviour appears at certain scales, while complex behaviour dominates others. Understanding increases when we recognise both as expressions of the same underlying order.

Space, Time and Layers of Meaning

Fractals appear in different domains. Mountain ranges and galaxies are patterns in space. Heartbeats and dripping taps are patterns in time. Market behaviour emerges in systems shaped by human expectations rather than by a single physical process.

Some patterns arise directly from physical mechanisms. Others arise from interactions between many influences. The price of a commodity, for example, reflects weather, politics, labour disputes, currency changes, and human beliefs about future events. Ideas themselves become causal forces.

We tend to regard physical objects as more real than abstract concepts. Yet both affect outcomes. Confidence, reputation, and expectation alter markets, politics, and behaviour. Reality therefore includes both material and relational layers. Events we observe result from interactions across many levels simultaneously.

Learning often follows this path. Children first recognise concrete objects. Later they recognise relationships and systems. Scientific inquiry seeks deeper organising principles that explain diverse observations through shared structure.

Fractal Generators and Fractal Compression

Once a system follows hidden patterns, we can describe it efficiently. Image compression uses this principle. Instead of storing every pixel of a photograph, software identifies repeating structures and stores rules that recreate the image.

This process works in two directions. Compression finds the rules from the image. Generation reconstructs the image from the rules. Rebuilding is computationally easy. Discovering the rules is difficult because it requires searching for structure.

As a thought experiment, imagine compressing larger and larger scenes. A small forest contains repetition. A landscape contains deeper patterns describing rivers, vegetation and terrain. If we could compress the entire universe perfectly, the resulting description would contain no redundancy. Every rule would be essential.

From this perspective, understanding nature means discovering patterns hidden within complexity. We do not derive them mechanically. We propose explanations, test them, and refine them. Science advances through this cycle.

Deductive and Inductive Thinking

These two directions correspond to two modes of reasoning. Deduction applies known rules to reach conclusions. Induction forms hypotheses from observation and tests them.

Deduction is reliable but limited to what is already known. Induction is uncertain but creates new knowledge. Effective inquiry requires both: intuition to propose explanations and logic to evaluate them.

Human cognition reflects this duality. Digital computers excel at rule-based operations. Pattern recognition, however, often requires systems resembling neural networks or biological perception. Animals survive through pattern detection rather than formal logic.

Human experience recognises this distinction informally. We speak of logical reasoning and “gut feelings.” Modern neuroscience confirms that complex neural processing occurs beyond conscious awareness and contributes to decision-making.

It Takes Years to Learn Cree

Languages emphasise different aspects of reality. Some focus on objects. Others emphasise relationships and actions. In verb-oriented languages, meaning is tied to processes rather than static things.

This difference shapes understanding. A culture centred on nouns highlights separate objects. A culture centred on actions highlights interactions. Each captures part of reality, but relational descriptions align naturally with a world organised through patterns and processes.

The well-known Sapir–Whorf hypothesis is often misunderstood as claiming language limits thought. A more reasonable interpretation is that language directs attention. What a language makes easy to describe becomes easy to notice.

Richard Feynman illustrated this when he said learning a bird’s name teaches little; observing its behaviour teaches understanding. Knowledge lies in relationships, not labels.

Computer Programming

Programming provides a practical example. A program is a precise description of behaviour. Poorly organised instructions interact unpredictably, producing complexity and errors. Well-organised structures reflect underlying relationships and remain manageable.

Effective designers look for the deep structure of a problem rather than simply adding features. They remove duplication and reuse general patterns. The result is simpler and more reliable systems.

This mirrors scientific discovery. Understanding collapses complexity into coherent structure. Without it, organisations accumulate procedures and bureaucracy. With it, a few well-chosen principles guide many actions.

Silver Cords, Clockworks and Bells

The same framework raises questions about consciousness. Earlier explanations invoked separate spiritual realms. Later explanations treated the brain as a machine whose operations produced awareness.

Neither approach fully explains subjective experience. Another possibility is that consciousness emerges from interaction between the nervous system and the vast flow of information surrounding it. The brain may not create awareness alone but may organise and interpret incoming patterns.

From this perspective, awareness resembles resonance: a complex system responding to structured input. The hypothesis remains speculative, yet it situates consciousness within the same patterned universe rather than outside it.

Magic and Arts

Historical traditions expressed similar ideas symbolically. Alchemical and mystical writings described correspondences between different levels of reality. Interpreted literally they seem obscure; interpreted as observations about pattern and relationship they become intelligible.

Creative arts operate similarly. Artists observe complex experience and distil it into concise expression. Scientists likewise compress observation into theory. Both identify structure within richness.

The difference lies not in subject but in method of expression. Poetry conveys relationships through metaphor. Science conveys them through formal models. Each attempts to reveal order underlying appearance.

Across disciplines the lesson is consistent: reality is not merely a collection of separate objects but a network of interacting processes. As understanding deepens, complexity becomes organised rather than overwhelming. The search for structure, whether in mathematics, nature, culture or creativity, is the beginning of understanding.

Originally written in the early 2000s and refreshed for publication in 2026. Companion pages for each section expand the discussion and provide modern context.